We often talk about the silos in organisations but we often ignore the spaces between the silos. These are dark ungovernable places that do not exist on any structure chart.

But if you’re customer or a colleague who gets stuck there, it’s a nightmare to get out.

Failures in service delivery are often attributed to individual incompetence or malicious intent, but as economist Dan Davies argues in his book, The Unaccountability Machine, the true culprit is often systemic design failure.

These flaws create a ‘structural pathology’ where negative outcomes are generated automatically, consuming vast resources and eroding trust.

To understand this pathology and how they interact, we must define three concepts: silos, accountability sinks, and failure demand.

Defining the Pathological Triangle

The term “functional silo syndrome,” was coined in 1988 by consultant Phil S. Ensor. Ensor was inspired by the appearance of grain silos on his visits home to rural Illinois. He used the structure, which keeps different grains rigidly separated, as a metaphor for modern organisations.

He described the “syndrome” as a damaging outcome of traditional functional structures, where specialised departments become isolated, fail to share information, and focus on their own narrow goals rather than the overall success of the company.

While modern institutions deal with highly interdependent problems, their organisational designs are often maladapted for cross-system collaboration. Siloed operations facilitate the pathology by obstructing coordination and filtering out negative feedback signals before they can reach decision-makers who possess the agency to respond effectively.

This fragmentation ensures that the negative consequences are often ignored across organisational boundaries. Who is accountable? No-one.

This siloed environment is the critical precondition for the formation of the accountability sink. Conceptualised by Davies, an accountability sink is a systemic phenomenon—an organisational structure where responsibility, while appearing to be assigned, is absorbed, obscured, or deflected when negative outcomes occur. The sink operates by delegating critical decision-making authority away from humans and into immutable rulebooks, policies, bureaucratic protocols, or automated algorithms. Accountability is diffused across multiple teams, displaced when blame is attributed to the rulebook, or absorbed into institutional processes, creating an illusion of control that masks genuine failure.

Crucially, the sink effectively severs the feedback loop, making it impossible to identify the source of mistakes and preventing essential organisational learning. The primary function of this mechanism, in a complex, risk-averse public sector, is not performance enhancement, but blame avoidance. When complaints increase it is common for an organisation to blame the public (‘everyone is complaining more’) or attribute it to ‘poor communication’ rather than seek out the root cause – the system itself.

The operational cost of the accountability sink is measured in failure demand. Coined by John Seddon, failure demand (or avoidable contact) is defined as demand on a service organisation that is caused by the organisation’s failure to do something, or to do something right, for a customer. This type of demand is distinct from value demand, which is the healthy request for the core service the organisation exists to provide. Failure demand includes rework contacts (fixing errors), missing information requests, clarification contacts, and progress-chasing (e.g. “Where’s my stuff”.)

The Causal Link: From Sink to Decline

The accountability sink functions as the structural generator of failure demand. When responsibility is diffused across multiple silos, the system lacks the integrated mechanisms needed to correct chronic flaws in service design. This systemic failure manifests as friction points for the user.

The volume of this preventable work is potentially staggering; studies show that failure demand consumes between 20 to 80 percent of organisational capacity, sometimes reaching 80 to 90 percent of contacts in local authorities.

A recent Home Office asylum service controversy—in which a £600 taxi journey was booked to take a person to a GP —exemplifies this pathology. The failure was organisational: the automated system only booked taxis due to rules requiring guaranteed transport (delegation to rulebook), and the ultimate accountable body admitted lacking aggregate data on taxi spend (absorption into a data void). The high-cost journey was the inevitable output of a system designed without effective cost feedback or cross-system coordination.

The Antidote: Focusing on Purpose

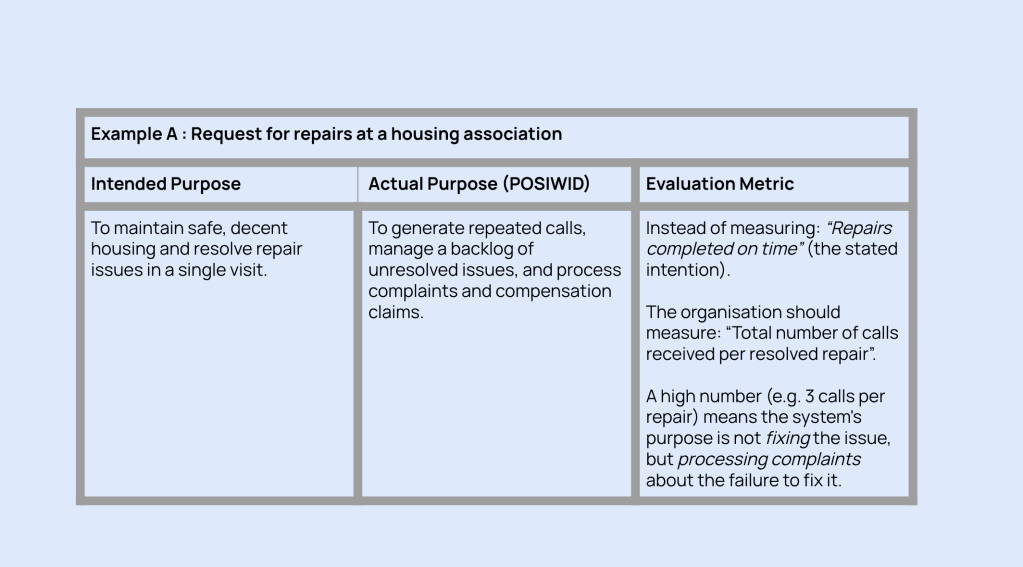

To make the shift, a structural redesign is necessary. The guiding principle could be Stafford Beer’s foundational maxim: “The purpose of a system is what it does” (POSIWID). POSIWID mandates that organisations should evaluate their success based on the actual impact and outcomes (like failure demand levels), rather than solely on the stated intention of the humans involved.

A similar maxim comes from Don Berwick who maintained that “Every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it gets”.

To bring this to life the following examples show the difference between intended and actual purpose.

Adopting POSIWID requires leaders to prioritise learning over blame.

Performance measurement must be holistic, promoting cross-system collaboration to mitigate the upstream problems that create failure demand.

Counteracting the ‘delegation to rulebooks’ requires enabling frontline staff to understand customer needs and adjust processes to solve complex issues, which is very much where we are going with place-based working.

The structural antidote to the silo-sink dynamic involves implementing robust cross-system coordination functions. This includes introducing systems convening roles or boundary spanners with authority to bridge organisational boundaries.

Instead of silos and accountability sinks we must build a “shared consciousness,” through the creation of a network of teams.

View the world as a system rather than a series of vertical silos, and keep an eye out for the people trapped in the spaces between them.

Image by Steve Buissinne from Pixabay

Leave a comment