Back in 2017, I stated something that was slightly provocative at the time:

Looking back now, as five years and more have passed, it’s clear: we did get it wrong. The public sector swallowed a dangerous pill disguised as progress – the digital by default hype. The idea was that all contact would be better – and cheaper – if digital was the default delivery model.

In a discussion last week with Tim Brooks and John Mortimer on LinkedIn, Tim said that the digital obsession was responsible for “leading to endless repeated examples of wasted money and idiotic fantasies about the necessity of IT to solve everything”.

Indeed, digital was touted as a silver bullet for efficiency and effectiveness, but as the evidence has mounted, it has proven to be anything but.

How We Chased the Private Sector’s Shadow

The allure of digital by default wasn’t born in a vacuum; it was a symptom of a larger, long-standing problem in the public sector: the uncritical copying of private sector practices.

This trend saw public sector leaders fetishising the likes of Amazon, Microsoft and Google believing that what worked for tech giants could be directly transplanted into complex public services. While there is nothing wrong with looking to the private sector for inspiration, the problem arose when this became blind imitation.

The fundamental flaw in this approach, as Jason Fried aptly puts it, is that “copying skips understanding”. When you copy, you miss the crucial understanding of why something works, merely “repurpos[ing] the last layer instead of understanding all the layers underneath”.

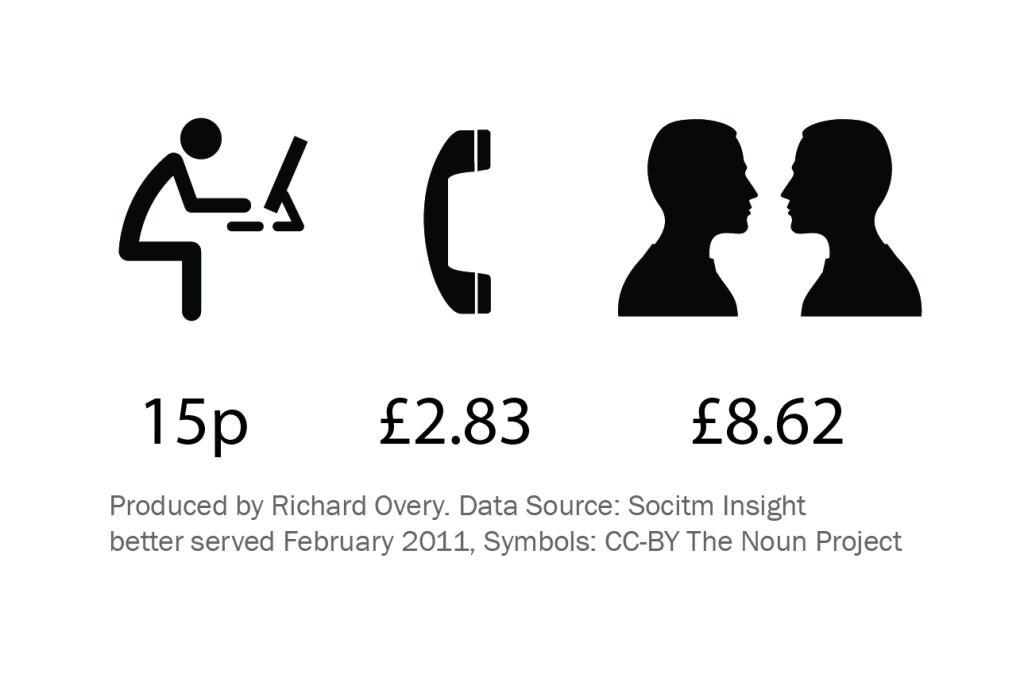

The allure of technology as a solution was persuasive though. You can see why people (including me) fell for the promise of a better world. Graphics showing the eye watering cost of face to face contact versus digital were enthusiastically shared around sectors by enthusiasts for this channel shift. I was as guilty as everyone else, until I started seeing bloated transformation programmes with no answer for more complex human problems.

As John Mortimer commented “those graphics had good logic, but were simply wrong because they treated demand as a simple transaction.”

This was the fundamental flaw of digital by default – the assumption that all users, regardless of their circumstances, could and would engage with public services digitally.

The model was largely driven by a cost-saving agenda, where the high expense of in-person interactions was the primary justification for pushing services online. The belief was that since digital channels are cheaper to operate, they should be the default, and any demand for face-to-face contact was an inefficiency to be minimised. This perspective failed to account for the diverse and often complex needs of the public.

The whole concept of face-to-face being an inefficiency failed to take into account that many interactions have a relational and human element.

These interactions are often complex, multi-faceted, and emotionally charged. In these scenarios, a digital-first approach becomes a barrier rather than a convenience. The transactional mindset fails to account for the need for human empathy, trust, and the ability to address nuanced problems that don’t fit into a pre-defined digital workflow.

There is no single public record that totals what has been spent on digital transformations across the public and non profit sectors in the past decade. We know that it is tens of billions , we just don’t how many tens.

We also know that productivity, user satisfaction and employee satisfaction has not risen in line with that huge investment.

The question is whether we learned from this.

From John Mortimer:

“I don’t see any real evidence of this systemic learning that is actively shared among those in the public sector. So, as we don’t learn, are we doomed to repeat the same mistakes? Maybe one of the most effective activities that the government reform group, or whoever, could do is to undertake this to learn deeply using a different mindset to those that have gone before.”

The cyclical nature of public sector failure is a testament not to a lack of intelligence or goodwill, but to a deeply ingrained resistance to genuine learning. It’s a system designed for stability, not innovation. The very structures that make it reliable—bureaucracy, risk aversion, and short-termism—are the same ones that guarantee we will, time and again, repeat the mistakes of our predecessors.

We are not just ignoring the lessons; we are actively disincentivised from learning them.

Unless , we do adopt a different mindset. This very discussion is evidence of a collective memory. We are not a blank slate. We have documented the failures, we have created the frameworks for success, and we have a growing cohort of people who are hungry for a better way. The shift we need to make is not in the grand, top-down mandates but in the small, rebel, grassroots movements.

We know where not to go, and now we have to draw a new map forward.

Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

Leave a reply to antlerboy – Benjamin P Taylor Cancel reply